Anyway, back to the original questions that began this thread –

Everybody seems to agree that, if the right to castle is temporarily lost in one position, and permanently lost in another, then the two positions are not identical (for triple-occurrence purposes). In fact, I don’t think any reasonable person would disagree.

There is, however, disagreement on what constitutes the permanent loss of the right to castle (for triple-occurrence purposes). There are two reasonable possibilities:

A. The right to castle is permanently lost (for triple-occurrence purposes) if either the king or the rook has moved from its original square.

– or –

B. The right to castle is permanently lost (for triple-occurrence purposes) if there does not exist a sequence of legal moves leading to legal castling.

LBLAIR asks the question, and seems (maybe) to favor definition A. GENE_M and TANSTAAFL definitely are in the camp of definition A. SLOAN (and RFEDITOR, until just now) do not weigh in on this issue, but seem to be overlooking something about the second example I presented. LBLAIR finally noticed this something, and observes that it casts his example and my second example as two instances of essentially the same situation.

In supporting definition A, TANSTAAFL points out that rule 8A3, which defines the permanent loss of the right to castle, is essentially the same as definition A.

This is not, however, a strong argument in favor of definition A in the triple-occurrence rule (14C). In fact, 14C never talks about permanent vs temporary loss of the right to castle at all. Rather, it says “the position is considered the same if pieces of the same kind and color occupy the same squares and if the possible moves of all the pieces are the same”. Here “possible moves” includes “future possible moves”.

Then 14C attempts to clarify itself, but succeeds only in muddying the waters, by adding the phrase “including the right to castle”. In implying that situation X includes situation Y, when in fact some elements of situation Y are outside situation X, this phrase in 14C worsens clarity rather than improving it.

In addition to the above, definition B is more in keeping with the spirit of 14C. If all the pieces are on the same squares and all possible future moves are the same, why shouldn’t the situation be considered the same?

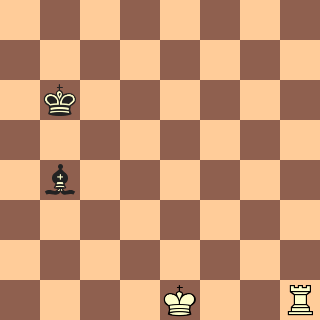

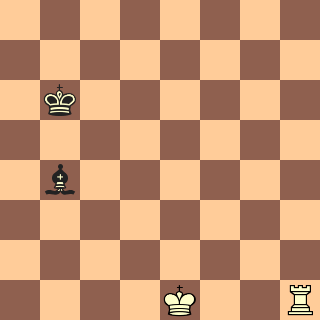

In LBLAIR’s example:

(neither K nor R has moved)

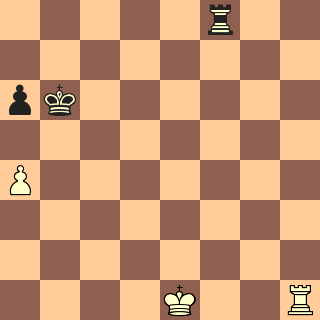

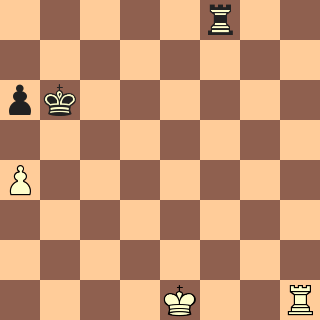

– and in my second example:

(neither K nor R has moved)

– there is no possibility of future castling (everybody please convince yourselves of this in the second example), so any repetition of either position after the king or rook has moved does not reduce future move possibilities. This, in my opinion, makes definition B more reasonable.

Bill Smythe